Link to LinkedIn thread

Link to Twitter (X) thread

There have been a number of op-eds and think pieces in the Irish media recently arguing to keep growing the data centre industry in this country.

A common thread among these articles is a claim that data centres are supporting Ireland’s energy transition, rather than working against our climate goals, as I and others have claimed.

These articles all share a similar line of reasoning: data centres support our energy transition and mission to decarbonise because they create a market for renewables (and thereby stimulate demand) and, digitalisation and AI can help solve climate change.

I want to take some time to look at the evidence behind these claims.

Take the headline of an op-ed written by Harry Goddard, chief executive of Deloitte Ireland in this week’s Irish Times: “Instead of curbing data centres, we should build more to spark greater demand for renewable energy”. The piece argues that the presence of more data centres will accelerate the development of renewable energy, and therefore their growth can be aligned with decarbonisation

Mr Goddard argues that limiting the expansion of data centres is “treating the symptoms rather than addressing the root cause” of our energy supply crunch, that Ireland’s per-capita electricity consumption is not among the highest in the world, and that data centres are necessary to generate revenue for renewables generation. In fact, he argues that the Government itself should be investing in and zoning land for data canters, and prioritising these and the necessary renewables and power grid as critical infrastructure (and presumably, be fast tracked through planning and permitting).

Similar arguments were made by Matt Cooper in this Sunday’s Business Post. Mr. Cooper quotes Pascal O’Donohue, Minister for Public Expenditure: “I believe [data centres] are the tangible reservoir of the ideas and intellectual capital that will change our economies” and argues that Ireland should “build, build, build, as many of these new data centres as possible, to surf that wave of where the AI revolution is taking the world”. Those who object suffer from “petty and narrow thinking”, according to Mr Cooper. The central claim of this article, like Mr. Goddard’s, is that not only is the expansion of data centres essential for Ireland’s economic prosperity, but this is also compatible with – or even necessary for - Ireland’s decarbonisation, as “data centre owners have been to the forefront of commissioning and paying for clean energy”.

Mr Cooper, in a follow-up debate with environmental journalist John Gibbons, even made the claim that most wind energy projects in Ireland are financed by data centres, and that they are run on “non-fossil fuels”.

These statements have been made but not backed up by any kind of serious analysis. The following are statistics and analysis I offer, which challenge the notion that such growth in data centres can be compatible with – or even support – Ireland’s carbon budgets.

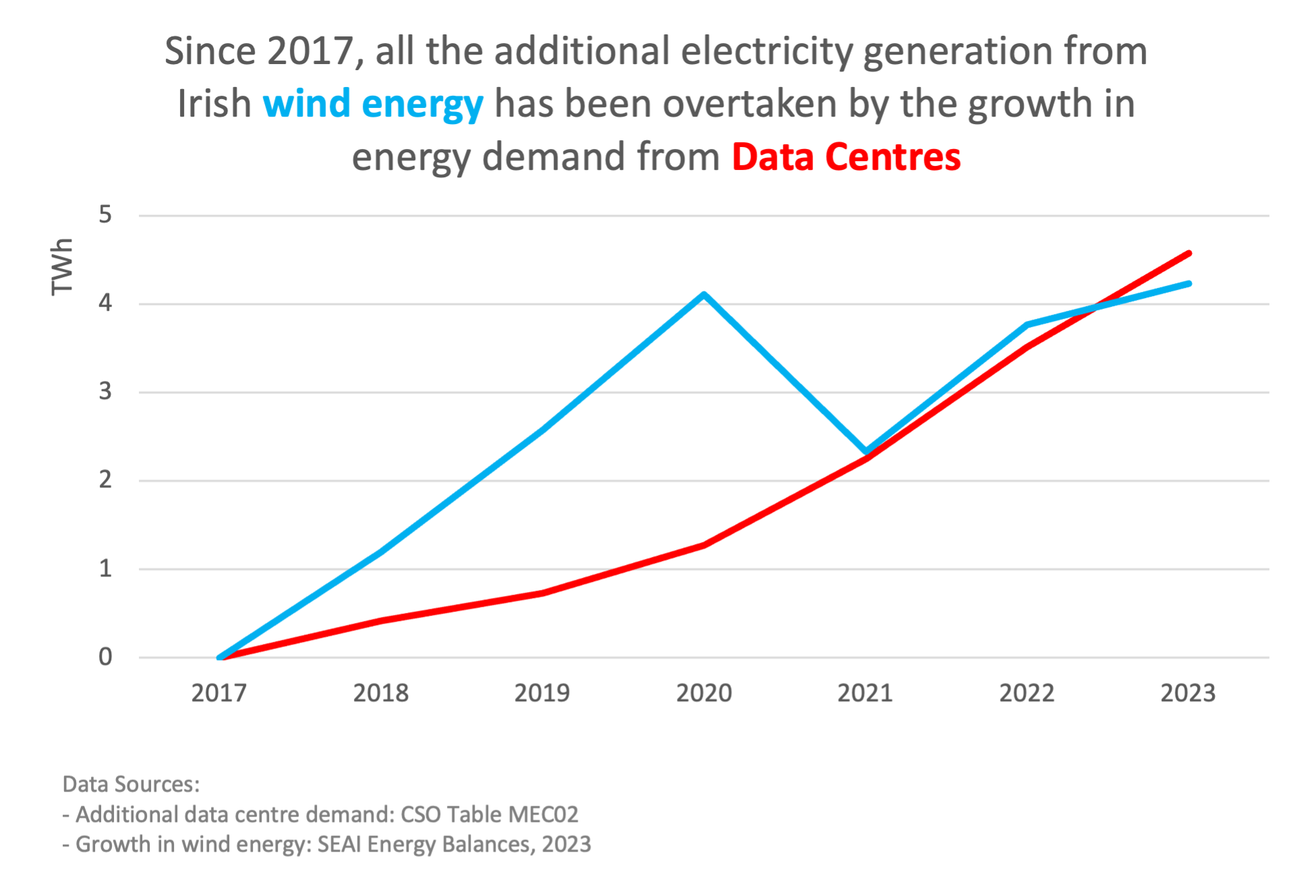

Growth in data centre electricity demand has entirely matched growth in wind energy production since 2017

Firstly, to support the notion that more data centres can accelerate decarbonisation, there would have to be evidence that renewable energy deployment is growing faster (or can grow faster) than energy demand growth from data centres, and that net renewables growth is greater than what it would be without data centres. This is because it is cumulative emissions that matter for the climate and the legal carbon budget basis for Ireland’s Climate Act – building renewables is only a means to achieve the goal of cutting cumulative fossil fuel use, and therefore carbon dioxide emissions. If growing renewables generation is simply met by growing demand, then fossil fuel use won’t fall – it will be like walking up a downwards-moving escalator.

When we look at the historical data and projections, there is no evidence to suggest that data centres are supporting renewables growth in this way. In the chart below I have graphed the additional wind energy generated in Ireland against demand growth from data centres since 2017. Data centres have more than matched all the growth from wind energy.

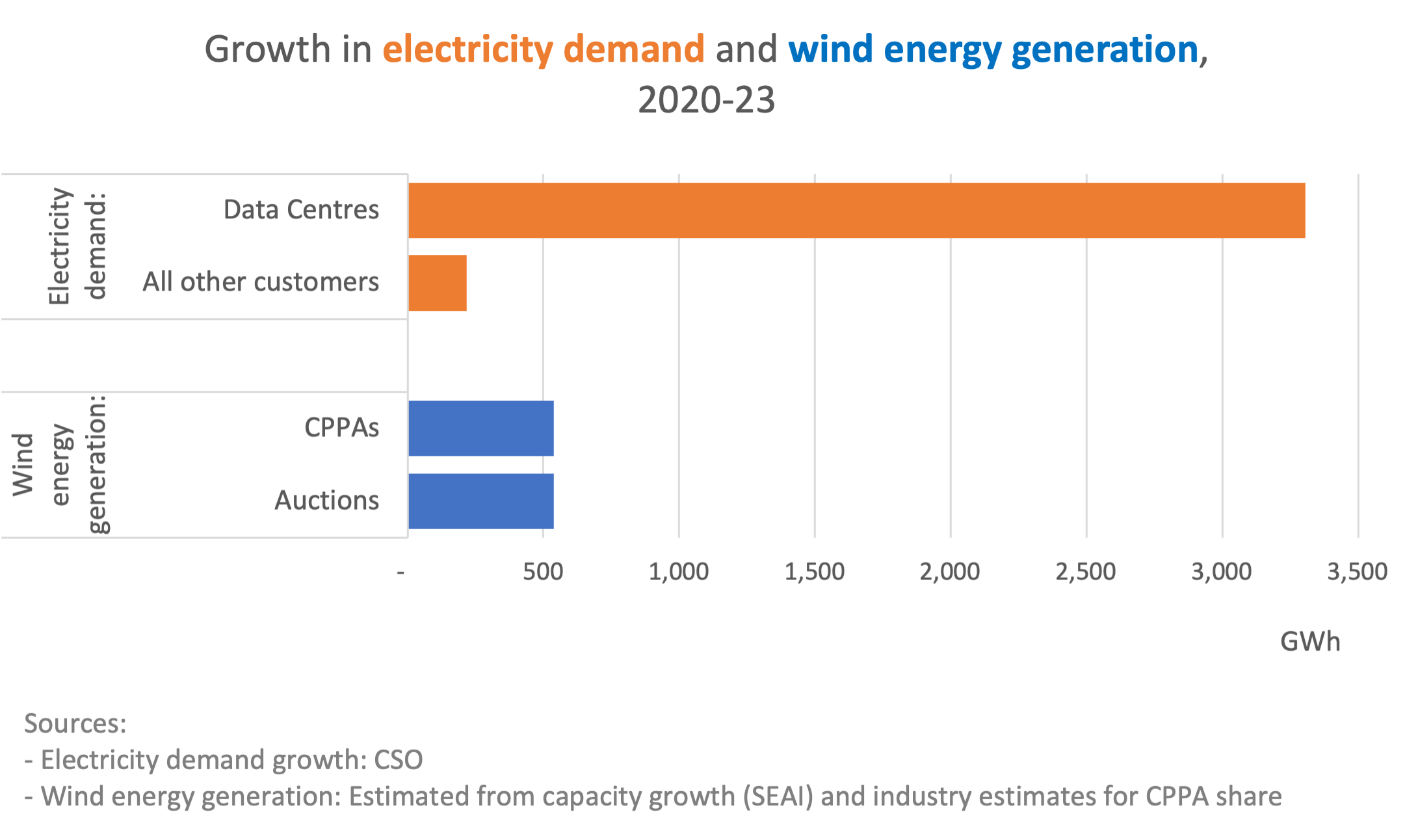

I estimate that CPPAs have only met 16 per cent of new data centre demand growth since 2020

Data centres have supported new renewables through power purchase agreements (PPAs, sometimes known as corporate power purchase agreements, CPPAs). This gives a new route to market for renewables projects beyond the Government’s Renewable Energy Support Scheme (RESS). In the chart below I estimate that only 16% of the new electricity demand from data centres since 2020 was matched by additional wind generation financed through CPPAs over that time. Data centre demand grew 6 times faster than new projects financed by CPPAs, and more than 15 times faster than electricity from all other sources – homes, vehicles, industry. I describe the methodology at the bottom of this post and welcome any additional data which would improve this estimate.

Unfortunately there is no central data source describing the financing of renewables projects (and if any reader has data to share, I would welcome it). From this analysis, it is clear that electricity demand from data centres is far outstripping the additional renewable energy being procured through CPPAs over the past three years, and the proportion of CPPAs undertaken by data centres is itself unknown.

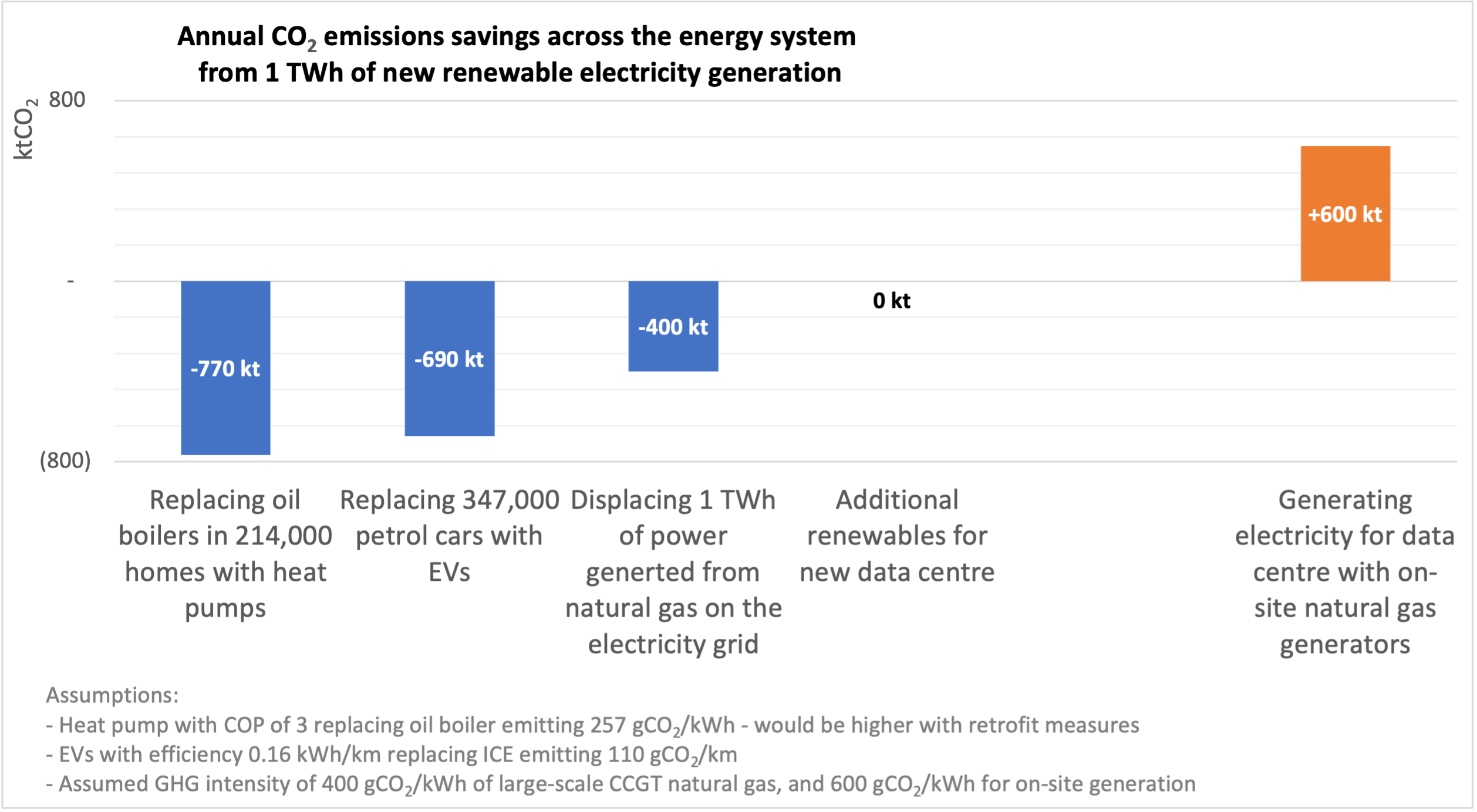

New renewables do not cause emissions to fall unless they are replacing existing fossil fuels

The narrative that procuring additional renewables capacity through CPPAs helps meet the targets under Ireland’s climate act is not valid, because total energy demand is rising much faster than additional renewables, and that energy has to be met through additional fossil fuels. As before, it is cumulative greenhouse gas emissions, not gigawatts of renewables capacity, that is the legal basis for Ireland’s decarbonisation commitments (and what matters for the climate).

In the analysis above, we see that the growth in electricity demand from wind energy generation from CPPAs met at most 16 per cent of the growth in electricity demand from data centres. If we assume that the remaining 86 per cent was met by the marginal generator, natural gas, with a CO2 intensity of 400 gCO2/kWh, this means that the additional power demand from data centres since the beginning of 2021 to the end of 2023 caused around 1.1 Mt CO2 emissions in 2023, which amounts to 2 per cent of Ireland’s entire GHG emissions, or 14.5 per cent of emissions from the power system.

If we look further back, and assume that 16 per cent of the power demand of all data centres currently in operation is met by “additional” renewables, procured through CPPAs, then the total annual climate impact is around double this – 2.1 MtCO2 - or 28% of the power system’s GHG emissions in 2023.

The graph below illustrates why it is so important, from a climate perspective, to focus new renewables on replacing fossil fuels than on serving additional demand from new data centres. It also illustrates why serving new data centre demand through on-site natural gas generators, which are less efficient than grid-scale generators, offsets huge emissions savings efforts from other sectors.

Renewables are necessary to decarbonise transport, heat, industry and power

Ireland has an abundance of renewable resources, but we have to look at the current reality rather than potential to get an objective picture of the climate implication of new data centres. Over 80 per cent of Ireland’s energy still comes from fossil fuels, and decarbonising our energy supply will require that new renewables are developed to fuel our existing demands – our cars, trucks, homes and businesses. R

There is already a huge market for renewables

There is a prevalent narrative that data centres support the renewables industry by forming a secure customer base. This is certainly true from the industry’s perspective – as above, around half of new onshore wind projects have been funded through CPPAs, a significant proportion of which are likely to be data centres. But there are a few counters to this argument. Firstly, it is total fossil fuel use that matter for the climate, and our legal carbon budget, rather than renewables investment – if renewables are simply growing to meet new demands then the climate is no better off. As I demonstrated above, data centre growth is far outpacing the new wind energy projects being brought about by CPPAs, and therefore the majority of growth is fuelled by fossil fuels.

Secondly, the renewables industry doesn’t need new customers to guarantee revenue – or it shouldn’t. In 2022, Ireland imported fossil fuels to the value of nearly €9 billion – over 80 per cent of our energy requirement is imported. This massive drain on people’s incomes and business’ profits is for fuelling cars and trucks, heating buildings, and powering industry. But instead, it can be fuelled by indigenous Irish renewable energy. There should be no shortage of new customers for Irish wind and solar projects as long as the electrification of heating, transport and businesses is completed and reliance on fossil fuels is cut massively. Once this is completed, ideally in the 2030s, then Ireland’s abundance of offshore wind potential may well be ideally suited to powering data centres. For now, arguing that we need more data centres in order to grow renewables is akin to arguing that we need new roads to support the growth of EVs.

These articles ignore that data centres are seeking to connect to the gas network

Climate is not the only constraint on the growth of data centres in Ireland – the physical capacity of the electricity grid is not equipped for such growth, especially in the Dublin area. To get around the effective moratorium imposed by EirGrid on new data centre connections there, developments are seeking connections to the natural gas network to generate electricity on-site through small-scale turbines. These developments have downplayed the climate impact of these developments because Gas Networks Ireland plans to decarbonise the gas network via biomethane and hydrogen (plans which I am personally deeply sceptical of – which I won’t go into in this blog post). Despite major concerns raised by the Climate Change Advisory Council and directions from Climate Minister Eamon Ryan, Gas Networks Ireland is advocating to allow these connections, which certainly contradicts any mandate it might have to support the achievement of carbon budgets.

Key takeaways

The Commission for the Regulation of Utilities (CRU) is soon due to finalise its Large Energy Users connection policy, as part of the National Energy Demand Strategy, which was a requirement under the 2023 Climate Action Plan.

In my view, even the projected growth of power demand from data centres with existing grid connections poses a major challenge to decarbonising our energy system in line with the Climate Law. Any new developments should be required to be 24x7 zero emissions from the point of operation and have an obligation to procure renewables in a way that is additional to, rather than in place of, renewables required for decarbonising the existing energy system. The practical implications of such a requirement would hopefully lead to an acceleration of the timelines of renewables, grid and storage developments, but it would also slow down data centre growth until we are on track to meeting carbon budgets.

Moreover, the idea of connecting new developments (or even existing customers) to the gas network is frankly alarming and flies in the face of the urgency of climate mitigation. That developments are even putting in planning submissions, and that GNI is advocating for this, shows very little faith in the “legally binding” nature of our carbon budgets, which is an ominous sign. It concerns me deeply that State agencies are supporting this, and promoting the narratives I analysed above. Beyond GNI, for example, Mr Cooper writes that “IDA Ireland is finalising its new five year plan at present to give to government, and it is certain to put this AI related investment front and centre”.

The theoretical demand for new data centres is difficult to comprehend – a video circulated on social media recently of former Google CEO Eric Schmidt saying that energy demand for AI is theoretically infinite. The idea that Ireland should offer our infrastructure and renewable potential, and sacrifice our climate goals, to meet this need is (to me) somewhere between bizarre and grotesque. AI is not going to help us secure a safe climate, and unless the industry is subjected to environmental limits it is going to make the situation much worse. I’m not advocating for “degrowth”, but for an enterprise strategy that doesn’t make our prosperity reliant on economic activities that work against our climate.

Note: Methodology for CPPA chart

Here, I calculate how much the historical growth in renewable energy capacity could have been financed by CPPAs, to estimate an upper bound for the share that data centres could be responsible for.

- According to industry sources, around half of the total additional wind energy capacity that has been energised since the start of 2021 have been financed through CPPAs. o SEAI’s Energy in Ireland reports that the installed capacity of wind energy increased by ~430 MW from the end of 2020 to the end of 2023 (significantly lower than the 600 MW annual growth in renewables capacity necessary to meet the Climate Action Plan targets).

- To overcome the variations from wind speed in different years, I assume a capacity factor of 29% (which was achieved in 2022). This implies that CPPAs were responsible for a growth in wind energy generation of ~220 GWh over these three years. Remember, this is an upper bound for the additional renewables generation procured by data centres – other industries also purchase electricity though CPPAs.

- At the same time, over these three years, power demand from data centres grew by over 3,300 GWh, while demand from all other metered customers grew by 218 GWh. This means that data centres electricity demand grew by at a minimum of 6 times faster than new renewables procured through CPPAs between the start of 2021 and the end of 2023, or in other words, CPPAs for wind energy met at most 16% of the growth in electricity demand for data centres.