Article published in the World Economic Forum on 20 June 2018.

Achieving universal access to electricity is essential for solving many global development challenges. Decentralized renewable energy technologies have emerged as a viable solution. Small, clean energy utilities called mini-grids are a key piece of the puzzle. They are community-based grids that generate and distribute power at the point of consumption. And they could be the most cost-effective way to deliver access to more than a third of the 1.1 billion people across the world who still lack any electricity supply, according to new analysis by the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Yet mini-grids are still largely an afterthought for many governments and their financial backers in Africa and Asia. Evidence strongly suggests that this mindset must change if the world is to achieve Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 7 - access to modern, affordable, clean and reliable energy for all by 2030.

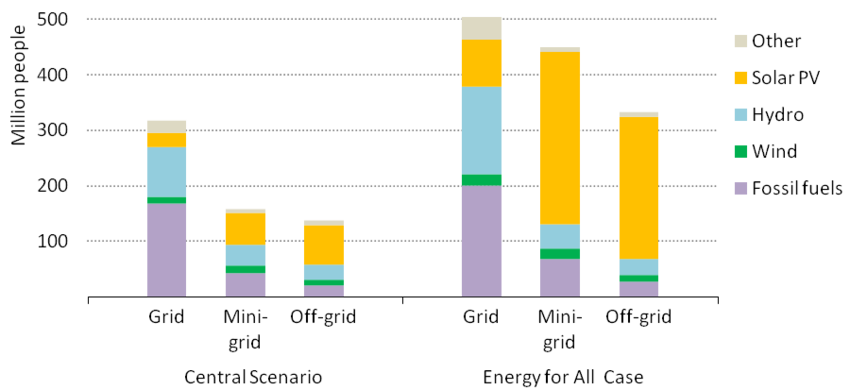

New IEA geospatial analysis, in an “Energy for All” scenario, shows that to provide universal electricity access to 1.3 billion people by 2030 (a number that includes projected population growth), mini-grids would be the cheapest technology for connecting 450 million people, two-thirds of whom live in sub-Saharan Africa.

However, current policies and investments would still leave more than 670 million people globally without access to electricity in 2030. Eighty per cent of these people live in rural areas of sub-Saharan Africa, severely limiting development prospects. Mini-grids are particularly well-suited for closing this gap, especially in remote areas underserved by grid infrastructure, offering an electrification option which can be faster and more affordable than extending the main grid.

Cumulative population gaining access to electricity by 2030

Image: IEA

Cumulative population gaining access to electricity by 2030

Image: IEA

Moreover, mini-grids have the ability to lay the foundation for development in rural areas, where more than four fifths of the world’s unelectrified live, by powering economic activities such as agriculture, business and small industry. These “productive uses” can provide consistent revenue to the mini-grid utility, thereby lowering the cost of electricity to households.

In the IEA’s “Energy for All” case, mini-grids would require a total investment of about $300 billion between now and 2030, or $20-25 billion every year. But to achieve this potential investment, governments need to put in place economic and policy frameworks to attract mini-grid developers, so that they can create economies of scale and attract the necessary commercial debt that usually supports energy infrastructure. In particular, that means creating certainty on rural electrification plans - including defining the planned roll-out of the centralized grid - and on tariff and subsidy regimes.

To ensure that mini-grids have a sustainable business model, work is also required to stimulate electricity demand from rural communities. Poor households often cannot afford or do not have access to appliances, beyond basic lighting and communications. Increased power consumption can be achieved by mini-grid utilities selling electricity services, rather than kilowatt-hours, to households, by financing appliances along with connections. This is a common business model for solar home system companies, enabled by mobile phone payments. Moreover, anchoring mini-grids to productive use sectors also increases their business case, providing a source of stable demand and revenue. This is especially the case for agriculture.

Scaling agricultural production is a critical element for Africa’s future development. Africa accounts for 60% of the world’s uncultivated arable land, and has among the lowest crop yields of any region globally. Less than 6% of farmland in sub-Saharan Africa is under irrigation, compared to 20% in the rest of the world.

As a result, Africa imports $35 billion worth of food every year, which is roughly equivalent to the investment needed to close the power deficit in Africa through mini-grids, off-grid home solar and grid extension. Food imports are estimated by the African Development Bank to rise to $110 billion annually by 2025.

Expanding rural electrification and powering agriculture, from solar-powered irrigation to cold storage to processing, can be achieved effectively with mini-grids, with much of the investment cost offset from increasing domestic food production. While policies are also needed to ensure infrastructure, develop markets and improve training to tip the scales on agricultural productivity, rural electrification is a critical factor.

Moreover, by scaling agriculture through clean, localized grids, demand for power would increase. This would not only bring down the costs for household access to power, but also enable the extension of electricity to street lighting, health clinics and schools.